- Blog

- climate change

- COP26? A...

COP26? A miracle if it doesn’t fail

Oct 28, 2021 | written by: Tommaso Ciuffoletti

On the one hand, there are all these positive proclamations in the run-up to COP26, everyone claiming to be ready to do big things to save our planet. Blablabla. And yet, on the other hand, there are increasing fossil fuel production plans for the coming years, and states paying subsidies to keep their prices down. If this is the situation, why would we be surprised if COP26 is a failure?

COP26 and structural limits

In my career as a journalist, I have been closely involved in the WTO (World Trade Organisation) negotiations of the so-called Doha Round. Launched in 2001, these negotiations were supposed to establish new shared rules for global trade in goods and also to regulate some decisive issues, such as the provision of agricultural and food production subsidies. The protagonists of these negotiations were the member states.

At that time, the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) were emerging countries and their main demand was to avoid being damaged by customs barriers for the export of their products and, secondly, to push the European Union and the United States to reduce the amount of subsidies paid to their agri-food sector (as these were considered to be distorting fair competition). On the other hand, the EU and the US asked the BRICs to avoid dumping and invading their markets with low-cost products, with serious damage to their own companies.

The result of this confrontation was a stalemate. The Doha Round negotiations came to a standstill in 2014 and since then nothing has been heard of them, while the world of global trade was being structured in an essentially anarchic way, with bilateral agreements between individual states or, at most, with regional alliances.

The lesson learned then was that although everyone paid lip service to the goal of a common agreement, in reality everyone was only looking out for their own interests. The structure of that negotiating system is similar, in its fundamental aspects, to that of the COP, which is entrusted with the hope of defining strategies for the containment of emissions and the fight against climate change.

This structure invites everyone to make grand public proclamations, while silently struggling to safeguard what they consider legitimate national interests. China and India, for example, are unwilling to give up the growth of their economies, powered by fossil fuels, blaming more mature economies, like the West, for polluting for much longer, without anyone holding them to account.

This is the first reason not to be optimistic about what will come out of COP26.

Fossil fuel production will increase

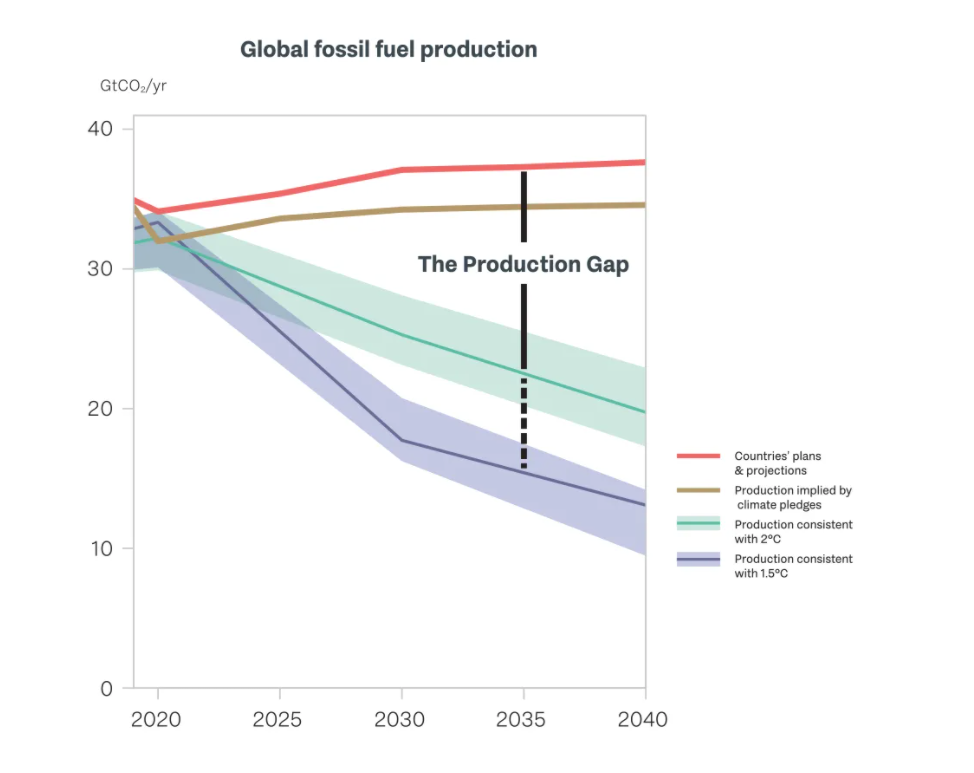

While countries are setting net zero emissions targets and raising their climate ambitions under the Paris Agreement, they have not explicitly recognised or planned the reduction in fossil fuel production that these targets will require. Instead, they plan to produce more than twice the amount of fossil fuels that would be compatible with limiting global warming to a 1.5°C increase.

This is revealed in the latest Production Gap Report - produced for the first time in 2019 - which tracks the discrepancy between fossil fuel production planned by the governments of 15 major countries and global production levels consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C or 2°C.

The countries covered by the research - including the US, India and China - are planning to increase global oil and gas production, and only modestly decrease coal production, over the next two decades. This will produce twice as much oil, gas and coal (until 2030) as would be needed to keep global warming below the 1.5°C threshold; a widely accepted limit if the world is to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

While great strides are being made against climate change, in practice much more is being prepared.

Fossil fuel subsidies

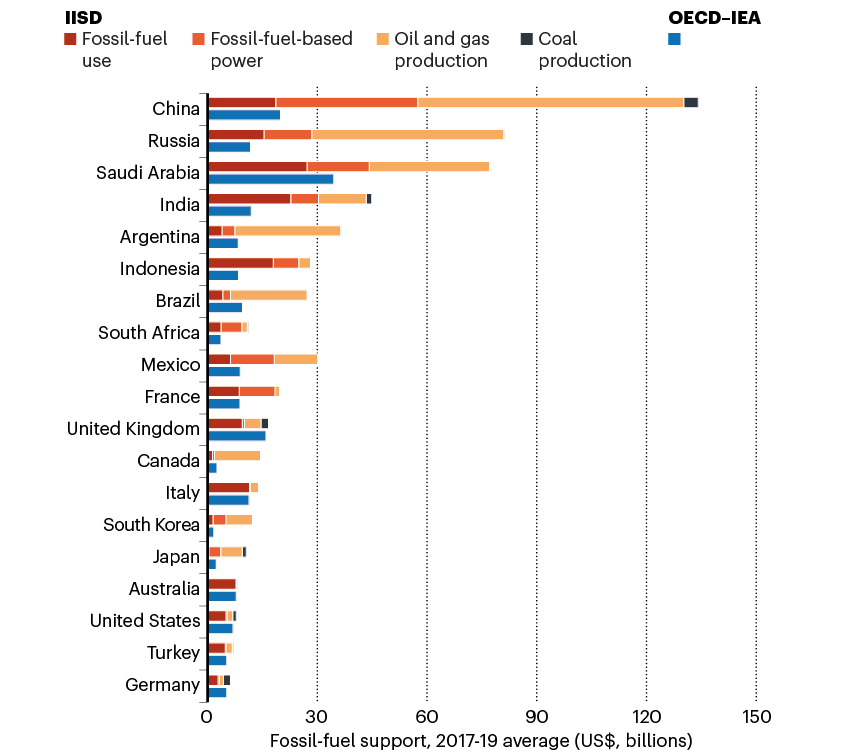

There is another aspect to consider, and it concerns finance. Fossil fuel subsidies are one of the biggest financial barriers to switching to renewable energy sources. Every year, governments around the world pay around half a trillion dollars to artificially lower the price of fossil fuels - more than three times what renewables receive. This is despite repeated promises by politicians to end such support, including statements by the G7 and G20 groups of nations.

A study by the GSI (Global Subsidies Initiative), supported by the International Institute for Sustainable Development, explains well how difficult it is to remove these subsidies. First of all, because identifying them is not easy, there is the problem of definitions. The G7 and G20 countries have promised to eliminate "inefficient fossil fuel subsidies", although they have not clearly expressed what this phrase means, with significant ambiguity about that word: "inefficient".

This leads to the paradox that some countries feel they have no subsidies to eliminate. The UK government, for example, says it has none, even though the IISD calculates that it spent $16 billion a year to support fossil fuels between 2017-19. In large part, this is because the UK foregoes some tax revenues from fossil fuel use and directly funds its oil and gas industry.

"They reject the idea that they are providing inefficient subsidies for fossil fuels," says Angela Picciariello, senior manager of climate and sustainability research at the Overseas Development Institute in London. So "it's quite difficult to engage with them on this.”

Moreover, each country has its own reasons for subsidising fossil fuels, often linked to its own industrial policies.

In conclusion

With all of this in mind, how can we feel optimistic about COP26?