- Blog

- biodiversity

- The scent of...

The scent of extinct flowers

Jan 31, 2022 | written by: Lara Zambonelli

Once upon a time there was an artist, a synthetic biology laboratory and an American herbarium. Between them, they recreated the scent of three plants that had lain extinct for decades. How – and more importantly why – did they do this? Let's find out.

Phantom scents

Hibiscadelphus wilderianus, Orbexilum stipulatum and Leucadendron grandiflorum: these aren't spells from Harry Potter, but rather plants that we only talk about in the past tense.

Having been extinct for at least a century, the last specimen of each of these plants had been dozing peacefully in Harvard University Library, forgotten by the world. That was, at least, until artists Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg and Sissel Tolaas, along with synthetic biologist Christina Agapakis, rescued them from oblivion with an ambitious and poetic idea: recreating their scent.

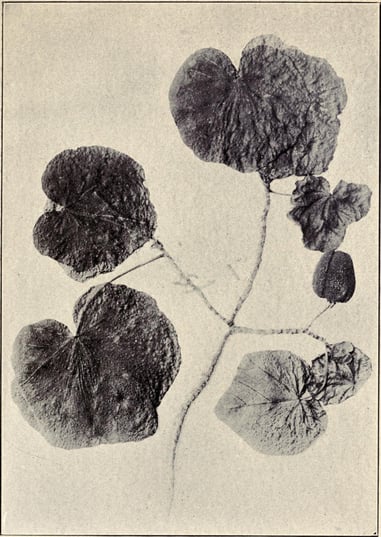

Hibiscadelphus Wilderianos (https://archive.org/details/newnoteworthyhaw00radlrich)

Hibiscadelphus Wilderianos (https://archive.org/details/newnoteworthyhaw00radlrich)

The group took samples of the plants from the rough, yellowed pages of Harvard University’s Herbaria, sequenced their DNA, and drew up a list of the fragrance molecules they contained. The list then winged its way to Germany, where artist Sissel Tolaas developed a “fragrance hypothesis” by drawing on her own incredible library of scents, built up over 25 years of research.

They unveiled the results of their project at a temporary exhibition entitled Resurrecting the Sublime, where visitors could immerse themselves in these lost scents.

Leucadendron grandiflorum was said to be reminiscent of tobacco, while Orbexilum stipulatum was apparently “citrusy and sweet-smelling”. Of course, this is purely hypothetical: while science can tell us which fragrance molecules made up their flowers, the exact quantity of each molecule remains impossible to reconstruct.

This is because extinction – from the Latin ex(s)tinguĕre, meaning “to fully extinguish” – is an irreversible loss.

Nostalgia for the future

Apparently, smells are among the most powerful stimuli for triggering memories.

So what’s the significance of breathing in the scent of a flower that died out more than a century ago? Why do we try to remember something that we have never experienced?

Perhaps we do this because we know we’re living in the lost world of the future. According to a 2020 study by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 40% of the plants that currently exist on Earth are at risk of extinction. The WWF and the IUCN (The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species) keep a logbook assessing the thickness of the thread from which each species dangles: vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered.

Royal Botanic Gardens di Kew. Credits David Hawgood, CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9338109)

Royal Botanic Gardens di Kew. Credits David Hawgood, CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9338109)

What’s the moral of this story? That interdisciplinarity is just a complicated word, one that means not approaching the world in a compartmentalised way, with science on one side and art on the other. And that the superfluous – like a project recreating lost scents – is actually necessary, because it stops us in our tracks and makes us think.

Sources

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/this-plant-no-longer-exists-but-you-can-still-smell-it

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/

- https://www.ginkgobioworks.com/2019/05/03/reviving-the-smell-of-extinct-plants/

- https://www.frieze.com/article/sissel-tolaas-re-2021-review

- https://www.tba21.org/#item--Smell%203_4--2164

- https://www.designindaba.com/articles/creative-work/scientists-and-artists-are-reviving-lost-scents

- https://www.resurrectingthesublime.com/about

- https://www.kew.org/science/state-of-the-worlds-plants-and-fungi